Posts Tagged ‘Canada Stamps’

How a £10,000 reward led to one of the greatest advancements in aviation

In the 1800’s, when aeroplanes were a mere twinkle in the eye of ambitious engineers, the idea of transatlantic flight came about with the advent of the hot air balloon. But one crash-landing, and one postponement due to the American Civil War meant this dream had to go back to the drawing board.

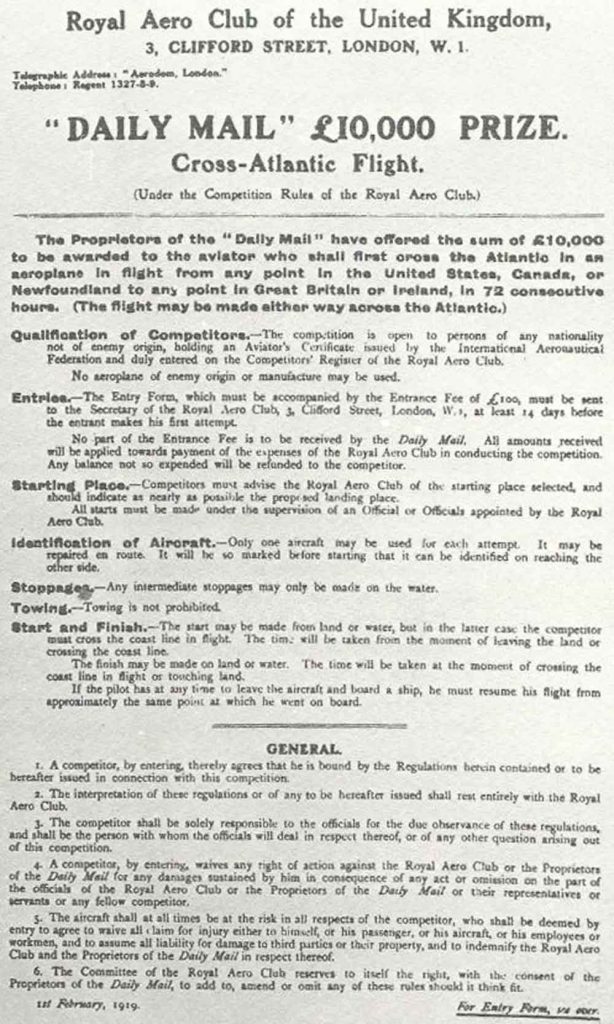

On the other side of the pond, in April of 1913 The Daily Mail newspaper offered a cash prize of £10,000 to “the aviator who shall first cross the Atlantic in an aeroplane in flight from any point in the United States of America, Canada or Newfoundland and any point in Great Britain or Ireland in 72 continuous hours”.

But it wasn’t until after the end of WWII that transatlantic flight by aircraft became truly viable, thanks to the significant advancements in aerial capabilities and technology.

Then the competition really heated up…

Nail-biting four-way competition

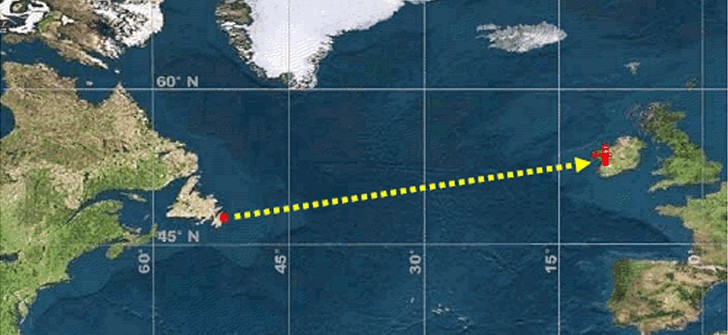

What came was a nail-biting four-way contest against the clock as well as each other. Four different ‘teams’ formed and went to work to try and prepare their chosen aircraft the fastest, for fear of being pipped to the post by another team making their attempt sooner. To make it a fair contest, each team had to ship their aircraft to Newfoundland for the take-off.

First to try was Australian pilot Harry Hawker and navigator Kenneth Mackenzie Grieve, piloting a Sopwith Atlantic – an experimental British long-range aircraft. In flight the aircraft suffered from engine failure and, when coupled with poor weather conditions, the decision was made to abort the mission.

The aircraft was abandoned in the Atlantic Ocean, 750 miles from Ireland, and the pair were rescued by a Danish steamer SS Mary. Due to the SS Mary not having any radio contact, the pair were presumed dead and King George V sent a telegram of condolence, but luckily this wasn’t the case as the pair arrived back on land nearly a week later.

The next attempt wasn’t nearly as exciting, as the aircraft never left the take-off zone. Frederick Raynham and C. W. F. Morgan made the attempt in a Martinsyde but crashed on take-off due to the heavy fuel load.

Then came the turn of aviator duo, John Alcock and Arthur Brown, who flew straight into the history books on June 15th 1919…

Flying in to the unknown across the Atlantic

The Vickers engineering and aviation firm, which had considered entering its Vickers Vimy IV twin-engine bomber in the competition, appointed Alcock as the team’s pilot along with Brown who was adept at long-distance navigation.

In preparation for the transatlantic flight, The Vimy, powered by two Rolls-Royce Eagle 360 hp engines, was successfully converted, including replacing its bomb racks with extra petrol tanks.

The pair took off from St. John’s, Newfoundland, in their modified bomber around 1:45pm on 14th June 1919. To say it wasn’t an easy flight would be an understatement. They encountered both mechanical and natural challenges. The wind-powered generator failed, depriving them of radio contact and much needed heating in their open-top cockpit. Fog and a snowstorm prevented navigation, almost resulting in a crash-landing at sea, not to mention the snow and freezing conditions meant the engines were in danger of icing up.

Whilst they were set a 72-hour target by The Daily Mail, the duo made landfall in Clifden, County Galway, in Ireland at 8:40am on 15th June 1919 – after just 16 hours of flight!

Incredibly, they landed not far from their intended landing zone in Ireland. However, the aircraft was damaged upon arrival because what looked like a field from their aerial view turned out to be a bog, causing the aircraft to nose-over. Thankfully neither were hurt, and Brown claimed that if the weather had been good, they’d have been able to continue to London.

A hero’s return to a £10,000 reward

Alcock and Brown’s successful attempt meant that the fourth team, Handley Page Limited, who were yet to take-off, were no longer eligible to compete. The two airmen returned home as aviation heroes and pioneers of the sky.

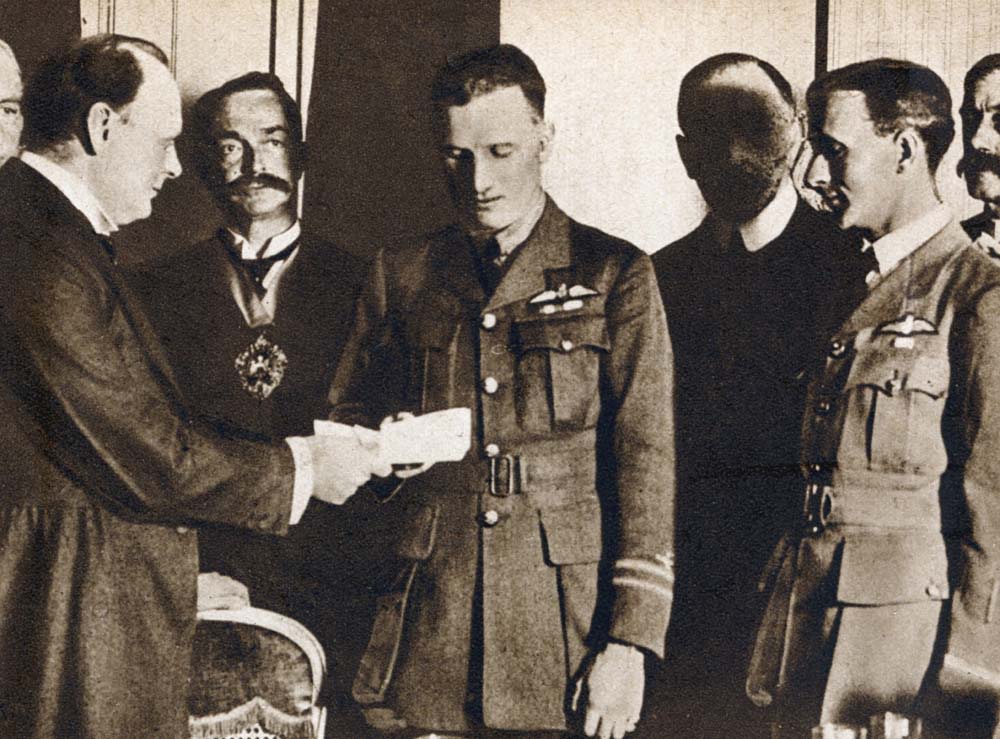

As promised, Alcock and Brown were rewarded for their ground-breaking achievement – the £10,000 prize money offered by The Daily Mail, for the first crossing of the Atlantic in less than 72 consecutive hours.

The Secretary of State for Air at the time, Winston Churchill, presented the pair with their cash reward. Then one week later, at Windsor Castle, they were awarded the honour of Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire by King George V.

If you’re interested…

The Royal Canadian Mint marked the milestone 100th anniversary of this remarkable achievement and feat of engineering with a limited edition 1oz Silver Proof coin. The coin features a faithful colour reproduction of the commemorative stamp that was issued to mark the 50th anniversary.

Unsurprisingly the coin proved so popular that it is no longer available at the Mint! We have a limited number remaining, click here for more information >>

Who issued the world’s first Christmas Stamp?

Did you know that since Royal Mail issued their first Christmas stamp in 1966, over 17 billion Christmas stamps have been printed in Britain? But as popular as they are today, Great Britain was late to the table when it came to issuing Christmas stamps. So which country can lay claim to issuing the first Christmas stamp?

The Contenders…

Canada – 1898

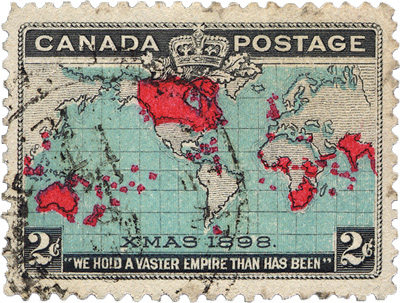

The first country to lay claim is Canada, which produced a stamp bearing the words ‘Xmas 1898’. But many people question whether this was really a Christmas stamp at all…

Denmark – 1904

Denmark claims it printed the first Christmas stamp in 1904 after an idea from postmaster, Einar Holboell, to add an extra stamp to the Christmas mail and the money go to help sick children. However these “stamps” were actually labels and not issued for postage.

Austria – 1937

Austria issued two stamps on 12th December 1937 for use on Christmas mail and New Year greeting cards.

Hungary – 1943

Finally, there is Hungary. Many people think the 1943 Hungarian stamps to be the first real Christmas stamps as they feature religious imagery.

The secret behind the Canadian stamp

It is fair to say however that the issue of the Canadian Christmas stamp did not really have much to do with Christmas. In fact it was a result of then Canadian Postmaster General William Mulock lobbying to standardise postage rates across the Empire at one penny.

After failing to get the new rules introduced at the 1897 Universal Postal Union, Mulock returned the following year more determined than ever, with a new proposal. This time he succeeded, and in July 1898, the Imperial Penny Postage rate was unveiled. Canada made the move to be effective on Christmas day 1898.

As a result, the stamp was officially released on 7th December 1898 bearing Mercator’s famous map with the British Empire highlighted in red, and also the words “XMAS 1898”.

So who can lay claim to issuing the first Christmas stamp?

Well despite the controversy, to me, there is only one winner – and that is Canada. Whether it was issued specifically for Christmas or not, it bears the words ‘Xmas 1898‘ and therefore I think it rightly deserves the title of first Christmas stamp.